Part 3 | Water Over the Dam (1900-1907)

Work scene at New Croton Dam, 1905.

Work scene at New Croton Dam, 1905.The New Croton Dam was built largely by immigrant labor. The majority of the workers were Italians; others were Irish, African Americans and Scandinavians. They lived in a number of small communities in and around the work site and in boarding houses located in the village of Croton Landing. At the foot of the dam, contractors had erected an office, commissary, clinic, and engine house for heavy equipment.

About one mile from the site along the banks of the Croton River was the Bowery, or Little Italy as it was also known. There were rooms for workers in two-story shacks, grocery stores, saloons, chapel and a one-room schoolhouse. Saloons tended to be tough places where fights broke out on a regular basis. One worker said, “It was a rough area. Fellas would get a few drinks, you couldn’t tell what the dickens they would do. There were murders and all sorts of things. It was a tough crowd and they couldn’t even talk English.”

Bowery supply bridge over the Croton River – used for men and equipment.

Bowery supply bridge over the Croton River – used for men and equipment.

Ignorant of the language and working conditions, eager not for permanent settlement but for immediate earnings to send back to their families, it was easy for workers—given the labor conditions around the dam—to fall into a pattern of subservience to, and dependence on, the “padrones”, bosses who exercised a form of control upon the men.

Italian workers’ community with New Croton Dam in background.

Italian workers’ community with New Croton Dam in background.

The padrones spoke English, hired workmen in large groups, charged them enormous commissions (having already advanced them passage money for the journey from Italy). They sold daily provisions to the workers at high prices and deducted a percentage from regular pay. Each padrone had up to 150 men under his direction, providing them board, lodging and laundry. The workers were paid once a month and were usually in debt.

Group photograph of laborers about 1905.

Group photograph of laborers about 1905.

Rooming houses provided the primary type of housing. They featured a long table with wooden benches on either side, able to seat 60 workers. Sleeping quarters were nothing more than canvas cots in one large room.

Dormitory-style housing along today’s Route 129.

Dormitory-style housing along today’s Route 129.

Some of the men sent for their wives so that they could establish a lodging house and earn extra money. These families took on boarders and provided meals, mending and laundry services. If the family operated a commissary, bakery or saloon, the wife assisted in that trade.

Quarryman Andreas Longo with family in 1900.

Quarryman Andreas Longo with family in 1900.

With the dam’s completion in 1907, most of the single workers moved on to other construction and railway jobs. Several hundred families remained to start new neighborhoods in the village of Croton.

Riverside Avenue along the Croton-on-Hudson waterfront.

Riverside Avenue along the Croton-on-Hudson waterfront.

The Italians were short-changed when it came to wages. “Intelligent labor” was paid 30 cents more per day than “common labor” but the common labor category was divided into white, colored, and Italian. Italians received the lowest salary. The laborers overall struggled with difficult working conditions. One or two would be killed, maimed or injured daily. Italians had a saying, “A man lost his life for every stone set on the dam.” Long hours and low pay created growing discontent.

Men working at stone quarry near today’s Route 202.

Men working at stone quarry near today’s Route 202.

A major conflict occurred in April 1900 when New York State passed a law making an 8-hour work day mandatory for all public works projects. An organized group of laborers subsequently agitated for higher pay along with improved working and living conditions. Contractors responded by announcing that there would be no raises, so a general strike was called. Workers threatened to blow up the dam structure.

Putting in pilings and support beams, 1900.

Putting in pilings and support beams, 1900.

Westchester County sheriffs were quickly brought in to protect the area. After several days with the fear of sabotage increasing, contractors asked Governor Theodore Roosevelt for military protection.

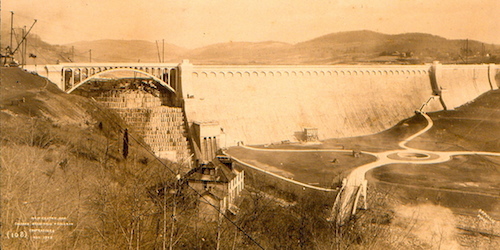

The project nears completion in 1905.

The project nears completion in 1905.

Roosevelt sent the Seventh Regiment, including cavalry and infantry, from New York City up to Croton. They came by train, marched up into the valley and set up Camp Roosevelt around the works project. Troops were also dispersed to protect the Old Croton Dam and smaller feeder dams that made up the New Croton Reservoir. After three weeks’ negotiations, the strike ended and the men returned to work, having achieved little to improve their working conditions.

Soldiers of the New York National Guard Seventh Regiment on Grand Street in Croton, 1900.

Soldiers of the New York National Guard Seventh Regiment on Grand Street in Croton, 1900.

The connecting bridge on top of the new dam ran into budget restraints so the design was changed a few times. Original plans called for a masonry arch across the gap in the spillway.

One of numerous designs for a connecting bridge on the New Croton Dam.

One of numerous designs for a connecting bridge on the New Croton Dam.

Another plan featured a curved framework, a third was highlighted by a single reinforced span, and a fourth, featuring a steel arch, was finally the one to be chosen.

The bridge rendering selected by resident engineers.

The bridge rendering selected by resident engineers.

The New York Times commented on the bridge in 1905: “Although the design for a steel bridge is graceful in itself, it forms a break in the masonry arrangement, which destroys the harmonious effect provided for in the original design.

Connecting bridge and spillway, 1907.

Connecting bridge and spillway, 1907.

Had the bridge been built by masonry and divided into panels, corresponding in width to the arches of the dam, the latter feature could have been carried across the dam and bridge, from abutment to abutment, with fine architectural effect.

Original bridge with spillway below.

Original bridge with spillway below.

These, however, are minor defects and do not prevent the Croton Dam from ranking, not only as one of the largest, but also one of the most handsome of this class of structure in the world.”

Aerial view of New Croton Dam and Reservoir, 2013.

Aerial view of New Croton Dam and Reservoir, 2013.

Over the years the bridge has been called the New Croton Dam Spillway Bridge, the New Croton Dam Bridge, and the Arch Bridge. The original span from 1905 was replaced in the 1980s and again in 2004, back to its original appearance.

New Croton Dam spillway bridge, 2013.

New Croton Dam spillway bridge, 2013.

The length of the dam across the Croton River Valley is 1,168 feet, spillway 1,000 feet, lowest point of the foundation 131 feet below the bed of the Croton River, ground level to top of dam 166 feet, total height 297 feet, thickness of the base 206 feet, thickness at the top 18 feet, and width of the roadway 20 feet.

New Croton Dam, Croton Gorge Park below.

New Croton Dam, Croton Gorge Park below.

One of the unique features is the s-shaped curve spillway, designed to be used as a waste channel for water coming over the top of the dam.

New Croton Dam spillway.

New Croton Dam spillway.

The last stone of the dam was put into place on January 10, 1906. A handful of engineers, contractors and workers were present to witness the occasion. New York City Mayor George Brinton McClennan Jr., son of Civil War Union General George B. McClennan, was invited but declined, saying that he was too busy, that there would probably be another ceremony at a future date.

The massive public works project in 1904.

The massive public works project in 1904.

Quoting from a newspaper of the period: “When the party had assembled at headquarters on the hill above the dam, they were invited into the dining hall, where they partook of a sumptuous repast. A number of guests were called upon for short speeches, some of them being solemn and impressive, while others elicited rounds of applause by their witty and humorous responses.”

Engineering headquarters overlooking New Croton Dam, ca. 1906.

Engineering headquarters overlooking New Croton Dam, ca. 1906.

One of the contractors spoke on the history of the project and remarked that there had never been a celebration of the anniversary of completion of the Old Croton Dam, some three miles upstream. He suggested such commemoration would be appropriate.

After lunch the guests were taken to the top of the structure, where they found a cut stone weighing 3,200 pounds, suspended by chains. New York City Comptroller Herman Metz gave a brief speech, accepted the New Croton Dam on behalf of the metropolis, drew from his pocket a genuine shamrock which he had brought from Ireland, and cast it beneath the stone. This was quickly followed by a shower of coins from the gathered guests.

January 10, 1906 – ceremonial laying of last stone on the structure.

January 10, 1906 – ceremonial laying of last stone on the structure.

Metz spread cement with a silver trowel and then raised his hand to give the signal. Workers nearby started the steam engine-powered machinery, and the last stone was lowered to its final resting place. This was followed by the breaking of a bottle of champagne, which was thrown into the deep hole, and the reservoir started to fill. The work of building the greatest dam in the world was completed.

Herman Metz brought from Croton to his home in Brooklyn a smooth fox terrier of doubtful lineage that had been presented to him by the dam’s contractors. When last seen at the dam, Metz was negotiating with an expressman to take the dog, named “Dam Site”, to his domicile.

Typical fox terrier.

Typical fox terrier.

The final stone on the spillway was laid one week later. Trowels with the inscription “Used for laying of last stone, New Croton Dam, January 17, 1906” were given to New York City in 1948 by Reverend Constantino Cassaneti, pastor at the chapel located along today’s Route 129 below the dam during the construction period. The Reverend mailed the trowels from Vatican City where he was residing at the time.

January 17, 1906 – officials placing final stone on the spillway.

January 17, 1906 – officials placing final stone on the spillway.

The New York Times reported: “Soon the once narrow Croton River will be a great lake, filling in the valley behind it for nearly 20 miles. When the waters have risen to the top of the new dam, the crest of the old dam will be 33 feet below the surface.”

New Croton Dam and Reservoir, 2013.

New Croton Dam and Reservoir, 2013.

The structure was officially declared completed, including the road across the top and the park with fountain below, and turned over to the City of New York on New Year’s Day 1907. The design of the New Croton Dam became a standard reference for gravity dams.

Postcard of newly completed New Croton Dam, 1907.

Postcard of newly completed New Croton Dam, 1907.

What became known as the “Croton Profile” achieved international recognition. At the time of its completion, it was the tallest masonry dam in the world.

An architectural review in 1907 stated: “The dam is very much a cleanly articulated, sculptured object in the landscape.”

An architectural review in 1907 stated: “The dam is very much a cleanly articulated, sculptured object in the landscape.”